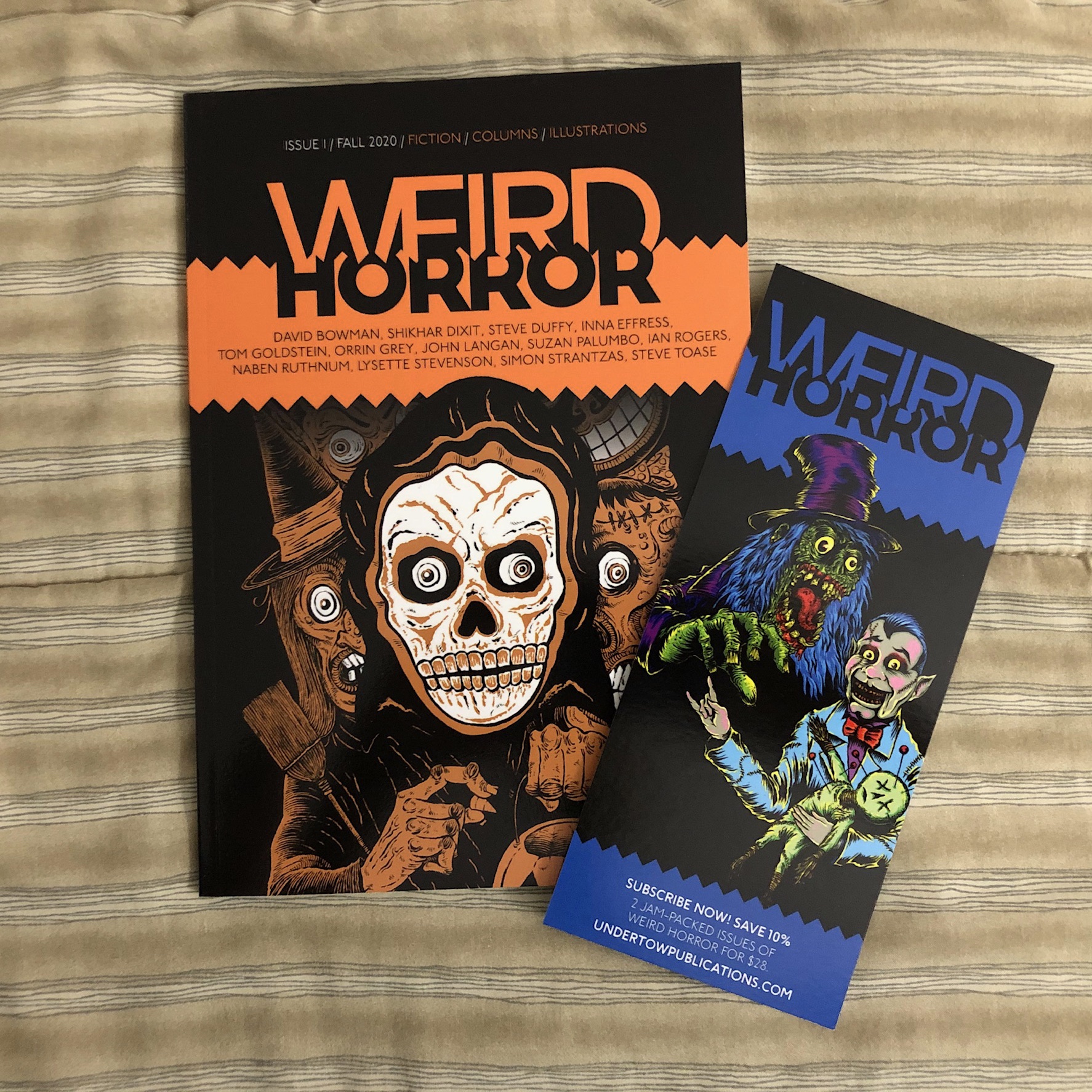

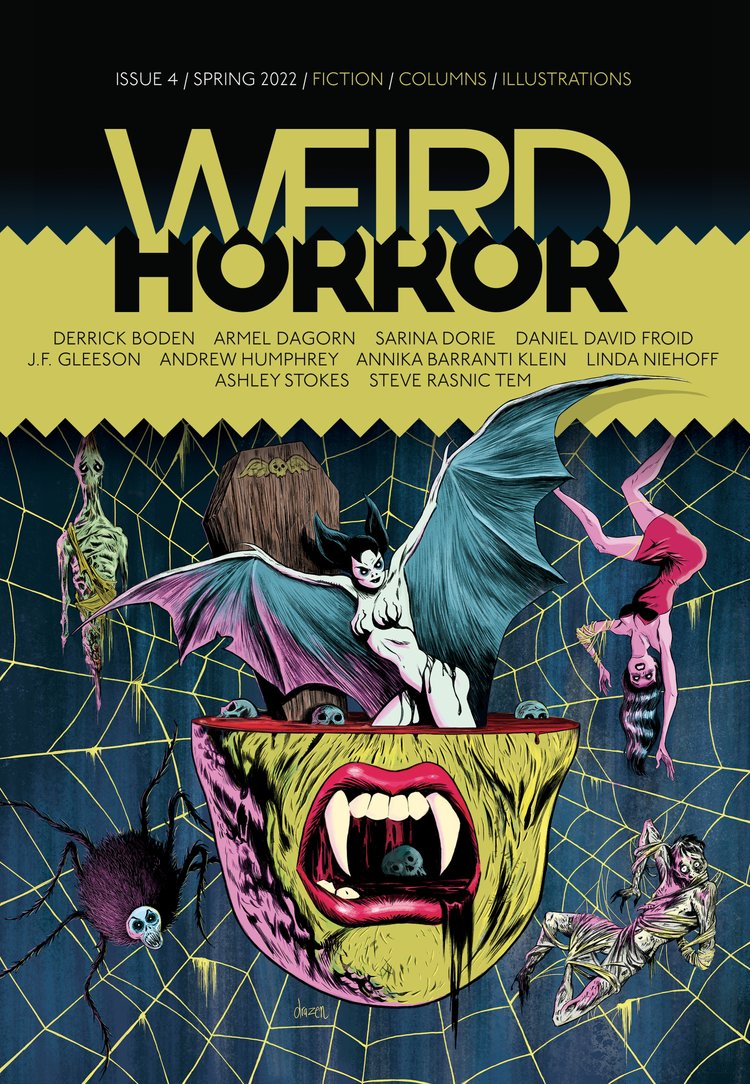

Weird Horror Issue 4/Spring 2022

Weird Horror #4 continues to evoke the deepest feelings of the most delicious dread two years since its launch. Some of the non-fiction and fiction contained herein:

Author/Editor/Horror Philosopher Simon Strantzas returns with another fascinating installment of On Horror. Next Wave Horror is the topic, and Mr. Strantzas clarifies immediately that if you are hoping for a treatise beginning with works of dread from Beowulf (666 A.C.E., for those who care) onwards, you should look elsewhere. The topic concerns the New Wave of the Genre of Horror, AKA Category Horror. Born circa 1970, the horror genre as we know it began with the publications of William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist, Thomas Tryon’s The Other, and Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby (do I detect a preoccupation with evil children?), all books by mainstream writers active in the early 70s. This concentration of horror novels resulted in the birth of First Wave Horror. The First Wave was defined by writers like Richard Matheson, Ray Bradbury, and Stephen King, as well as certain recurring concepts like twist endings and unpleasant children. The First Wave, Mr. Strantzas states, “remains the most popular form of horror story in the mainstream.” The nearing end of the Twentieth Century gave rise to Second Wave Horror, with young writers never knew a time prior to the horror boom of the First Wave (which I personally feel damaged the genre, due to the publishing industry’s preference of quantity over quality), and thus moved to a less literal, more metaphorical, more pessimistic (realistic) view of the vast cosmos and our miniscule part in it. I think Mr. Strantzas alluded to the fact the Second Wave horror writers add a more literary sensibility to their dark works. Here, Mr. Strantzas gave a nod the my favorite of the Second Wave authors, the largely mysterious Thomas Ligotti (I used to carry around my copy of The Nightmare Factory, or as I called it, the Gospel of Thomas, everywhere I went.) Twenty years after the birth of Second Wave horror, Mr. Strantzas states his belief that “we’re about to experience another shift led by a new wave … already percolating up through the small presses.” He does acknowledge the possibility that our much faster-moving society and culture could leave us “instead just a steady and constant onslaught of new writers and new kinds of work, a state of constant flux and noise, one that will be impossible to parse. Because it’s so overwhelming. A world where everything that can exist will exist and all at once.”

Orrin Grey, in this issue’s Grey’s Grotesqueries, makes the argument that in fiction, funny, silly or goofy incidents, or characters, do not necessarily dispel terror. In this highly persuasive argument, Grey posits that horror fiction where the artist diligently avoids even a dash of humor ends up with “somber meditations on grief, or bloody and brutal depictions of ostensibly realistic violence.” We’ve all seen those types of films. They are exhausting, perhaps disturbing, but have you ever wanted to give them a second viewing? I know that I haven’t. “Humor and horror, then, are…practically two sides of the same coin.” That one I intent to print out in huge letters and hang over. My writing desk! He mentions two masters at flipping that particular coin, the manga writer and artist, Junji Ito and author Matthew M. Bartlett. He ends by quoting an artist I’d never heard of, Trevor Henderson. The quote is illuminating and seals the cap of Grey’s cogent, highly convincing contention. But in order to read it, and to see the frankly horrifying reproduction from one of Junji Ito’s panels, originally published in one of his collections from Viz—you need to pick up a copy of Weird Horror Issue 4, available at:

https://undertowpublications.com/shop/weird-horror-4.

I do not review short stories, as they generally speak for themselves, but of the 10 entries in Issue 4, all of which were satisfactory, special kudos are extended to Armel Dagorn for his story “Figments of the Night,” to the always fascinating Steve Rasnic Tem for “Whenever it Comes,” to Andrew Humphrey for the thoroughly chilling “Hurled Against Rocks.” And to the single most effective story in Issue 4, “Camera’s Eye,” by Daniel David Froid. This ghastly descent into darkness, both literal and figurative, would not leave my mind for three sleepless nights! Froid maintained absolute control over every element in his story, and thus over the reader. I will be seeking Daniel David Friod’s first collection, as soon as it is published.

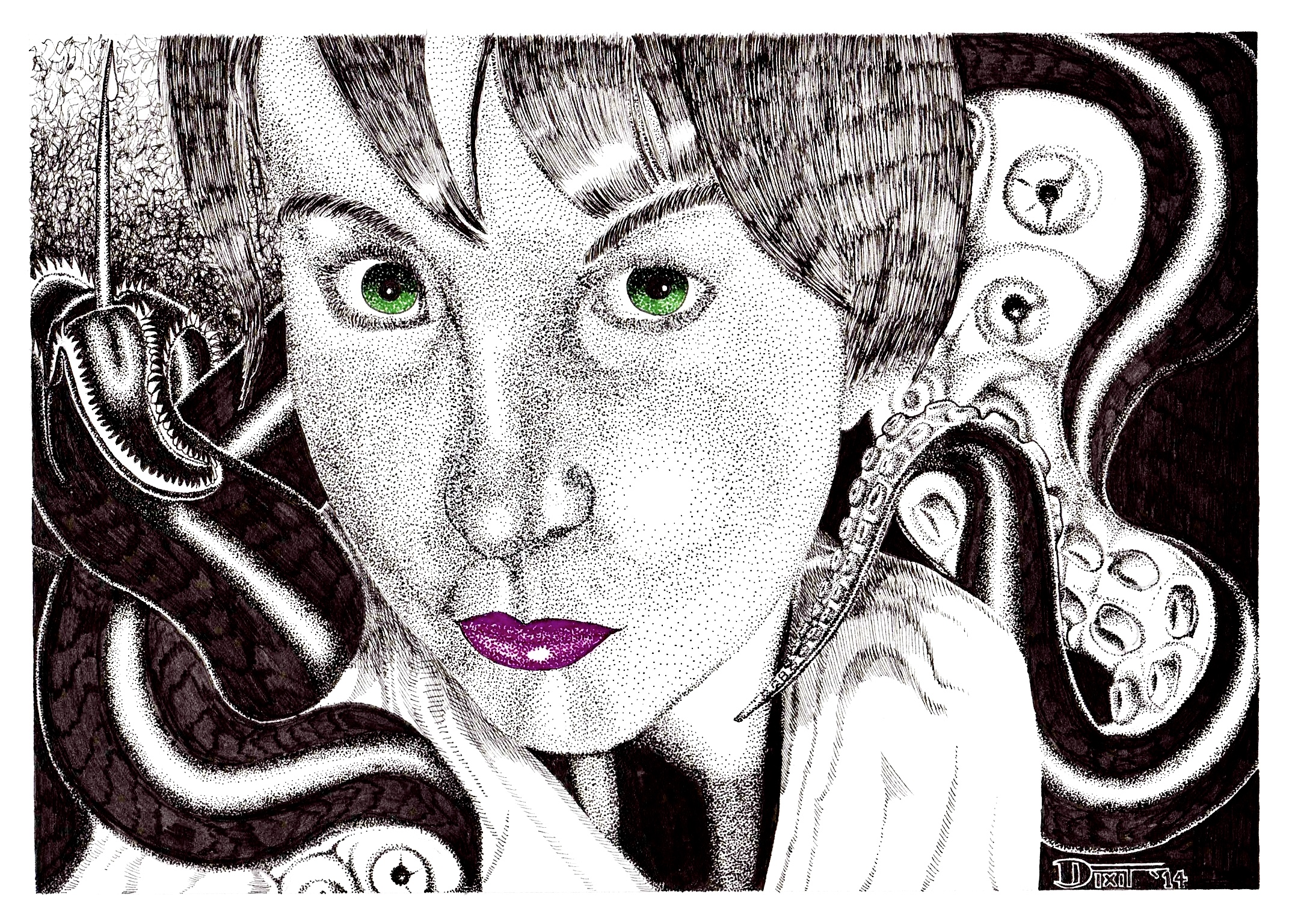

The story illustrations were competently rendered, by artist David Bowman, in a consistent hatching style. Also eye-catching is Drazen Kozjan’s perfectly pulpish cover illustration.

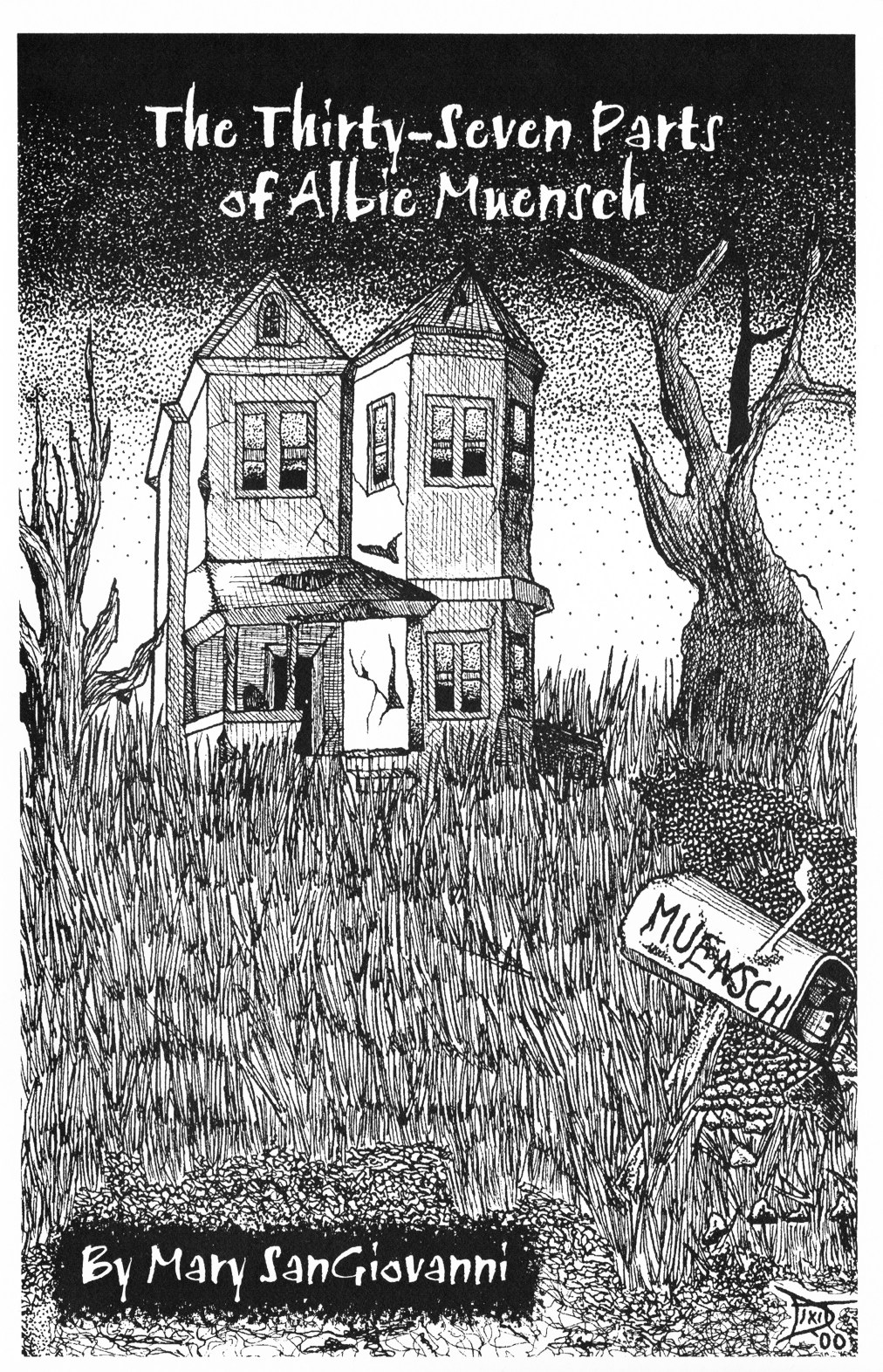

These fine stories were followed by the book review section, “The Macabre Reader,” more then ably handled by Lysette Stevenson. I love the fact that this section suggests new reading material in the horror/weird fiction fields that would not necessarily be evaluated in other journals. She does not waste time covering the latest Stephen King or Dean Koontz novel, as many other sources have already jumped on those books prior to their publication.

Similarly, Tom Goldstein fills his “Aberrant Visions” column with out-of-the-way films of the macabre, including quite a few foreign films. I don’t usually read the review sections of genre magazines, but Weird Horror’s inciteful and sometimes shudder-inducing book and film reviews are worth checking out. There are always a couple of offerings in each column that turn out to be worth their weight in blood, dissolved musculature, ligaments, and crushed bone!

At this point, none of the issues of Weird Horror have arrived late, unlike some other horror magazines I might mention. Editor Michael Kelly has proven that Weird Horror is also reliable in delivering the highest quality literary pulp horror and weird fiction, in a consistently attractive package. I think this magazine is here to stay.

Special thanks to Angela Yuriko Smith, Gerard Houarner, and Diane Weinstein (and Lee) for this incredible opportunity.

Special thanks to Angela Yuriko Smith, Gerard Houarner, and Diane Weinstein (and Lee) for this incredible opportunity.